THE SERIES

- Part 1: Optics Buying Guide: Iron Sights, Red Dots, and Scopes

- Part 2: Optics Buying Guide: Top Must-Know Terms for Picking the Right Scope

- Part 3: Optics Buying Guide: Scope Mounts

- Part 4: Optics Buying Guide: How To Properly Zero Your Scope

- Part 5: Optics Buying Guide: Finding Your Range with a Scope Reticle

- Part 6: Optics Buying Guide: Hold Off vs. Adjustable Scope Turrets

- Part 7: Optics Buying Guide: Scope Reticles

- Part 8: Optics Buying Guide: Using a Laser Rangefinding Scope

- Part 9: Optics Buying Guide: Holographic and Red Dot Optics

- Part 10: Optics Buying Guide: AR-15 Optics and Scopes

- Part 11: Optics Buying Guide: Big Scopes

- Part 12: Optics Buying Guide: Do You Get What You Pay For?

Today, shooters are blessed with a sometimes overwhelming number of gear possibilities to fir a broad range of field, plinking, defensive and competition scenarios. Even when you narrow the accessory universe down to sighting options, you’re still faced with iron sights, traditional red dot (reflex), and magnified scopes. Choosing the right type, or combination of types in some cases, can be a bit of a mystery. We’re going to take a look at some of the major types of optics here and detail scenarios where each makes sense.

This is the first installment in a 12-part series on optics and all things related. It’ll be kind of like going back to school, although way more fun. We’ll get into all sorts of geeky optical sighting topics like focal planes, reticles, exit pupil, minutes of angle, and even milliradians, but I promise up front, there will be no hard math. Unlike your algebra teacher, I can guarantee that all of the topics we’ll get into will be immediately useful in real life, or at least on the shooting range.

To kick things off, let’s we’re going to hit the basic definitions and pros and cons of iron sights, red dot sights, and scopes along with some discussion on when and why you might choose each.

Iron sights

Using iron sights is traditional, badass, and, therefore, cool, right? They never run out of batteries and if they’re made of something durable like steel, you can bash them about and they’ll never let you down. But have you ever thought about the science of what makes iron sights work, and, (gasp!) why they might be less than ideal?

A protected iron post front sight like this one on my Ruger 10/22 is plenty durable and reasonably fast.

The key to iron sights is the “s” as in the plural part. An iron sight won’t do you much good. Imagine a bead on the front of your rifle, with nothing but oxygen and your eyeball in the back. You can place the bead on target, but if your head moves so much as a millimeter up, down, or to one side or another, you’re no longer in alignment with the target. It works OK for shotguns, but not so much for precision rifle shooting. To get the barrel pointed exactly at your target, the gun needs two points of reference. Those two things, front sight and rear sight, need to align with each other. Then, both of those need to align with the desired target.

While reliable, iron sights are awfully demanding. They assume that you, the shooter, will be able to switch your eyeball focus rapidly between the front sight, the rear sight, and the target. Your eye can only focus on one thing at a time, because… biology. However, your brain fakes you out and makes you think that all three objects (front sight, rear sight, and target) are all in focus because it’s quickly switching back and forth between these three points. That gets tiring, even if you don’t realize that the eye / brain ADD festival is going on. Sure, with practice and training, you can force your brain to focus only on the front sight, while allowing it to let the rear sight and target be slightly out of focus. But that’s unnatural to our pre-existing eye-brain wiring.

Using an aperture for the rear sight makes things easier on your brain. It naturally centers the front sight post in the middle of the aperture ring.

I should mention a different type of iron sight setup that is easier on the eyes and brain – aperture sights. In this setup, the rear sight is a ring. Look through that to see the front sight and target. The beauty is that your brain naturally wants to center the front sight in the aperture, so you really have to worry about only the front sight and the target.

If you’re contemplating an iron sight setup, one important thing to consider is sight radius. This is simply the measurement between the front and rear sight. The longer it is, the easier it is to shoot accurately. Consider this. With a two-inch sight radius, a one-millimeter movement of the front sight off target will result in a miss by almost 18 inches. The same 1mm shift on a pistol with a six-inch sight radius will only result in a 5.9-inch miss. Now think about a rifle, with a 16 or 20-inch sight radius. It’s far easier to be accurate when the sights are farther apart.

When to choose iron sights:

Not so long ago, you could make a case for choosing iron sights simply based on durability. With just a few barely moving parts and no delicate electronics to worry about, iron sights were the “durable” choice. You never (well, very rarely) had to worry about iron sights failing you in time of need. Perhaps that’s once of the reasons that you still find iron sights on fancy double rifles designed for dangerous game safaris. There are still reasons iron sights are desirable, but durability is no longer at the very top of the list. Some of today’s red dot sights can handle incredible abuse and keep on ticking. With battery options that can last years, running out of juice is no longer the risk it once was.

A benefit of iron sights is that you have unlimited field of view at any range. This makes them excellent choices for finding and hitting moving targets. There’s no tube or optics body to block your view side to side. That’s why you’ll see iron sights on handy plinking rifles like the Ruger 10/22 shown here. On the downside, precision with iron sights is limited by the quality of the shooters eyesight. Trying to keep front sight, rear sight, and target perfectly aligned at distance remains a challenge. The bottom line is that if you have a need to hit close range and/or moving targets with a moderate degree of precision, then iron sights could be a good choice.

Red dot sights

Red dot sights are a nifty invention that completely do away with the multi-focal point challenges of iron sights. In this setup, a small red LED light in the base of the optic shines up at an angle directly at a very clever mirror. This mirror is coated so most light passes through, allowing you to see the target through it. However, red light is “bounced back” to your eyeball. The result is a red dot that hovers in space and appears to rest right on your target. That red dot sits at infinity so your eye only needs to focus on the target. Whatever the range of your target, the red dot is in focus right on it. The other neat thing about red dot sights is that they are parallax free for practical purposes. Don’t know what parallax is? Read on, we’ll get to that in a minute.

Using a zero magnification red dot sight like this Burris FastFire 3 supports your natural tendency to focus on the target and there are not three different focal points (front sight, rear sight, and target) to worry about.

For many applications, red dot sights are easy and fast. There is no need to align sights. If you can see your target and the dot, things will work out, whether or not your eye is perfectly aligned with the optic.

When to choose a red dot sight:

The base technology used in a standard reflex-style red dot sight is similar to that used in heads-up display systems in things like fighter aircraft and some modern cars. The whole idea of those is to allow the pilot or driver to focus on what’s out there rather than on the screen.

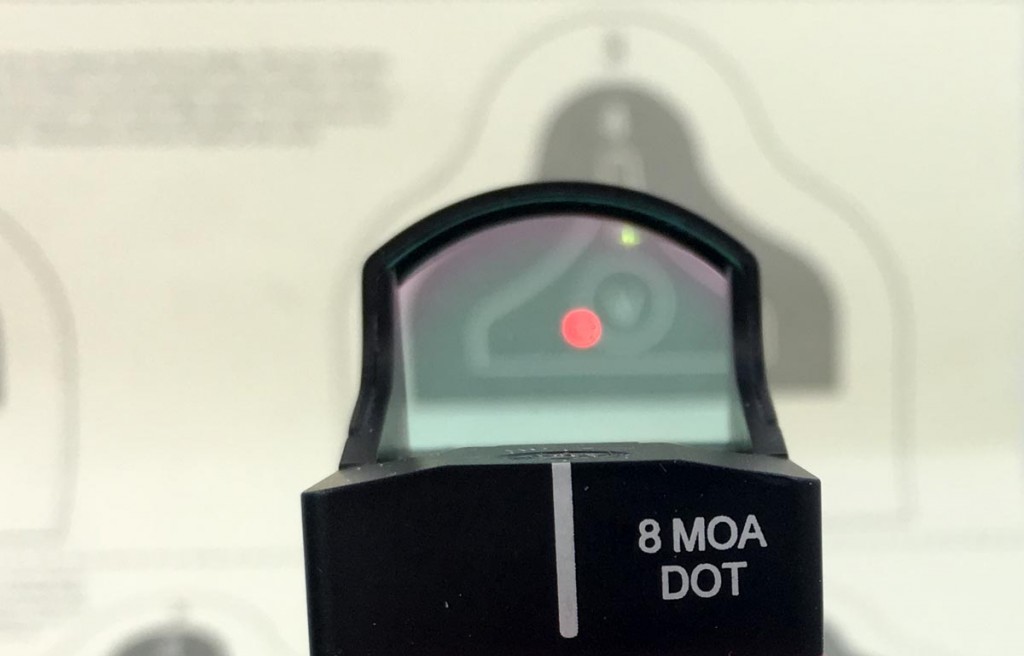

Modern red dot sights like the Burris FastFire 3 have no tube to block peripheral vision. This means that they have the infinite field of view benefits of iron sights with the additional benefit of an easier and faster aiming sequence. They’re designed to be used with both eyes open, so finding, tracking, and targeting moving targets is fast. Additionally, the small one to four minute of angle typical dot size gives you excellent precision out well past 100 yards.

If you’ve got an AR type rifle, it’s hard to argue against putting a red dot sight on it unless the majority of your shooting will be farther than 200 yards. With a red dot like the FastFire, you’ll be able to shoot with both eyes open and target and hit from three yards to 200 with ease and speed. Red dot sights also make a great combination with scout rifle setups where the optics mount is in front of the receiver. Short range hunting scenarios, regardless of caliber are also great for red dot sights for the same reasons.

Scopes

The neat thing about scopes is that the magical lenses inside give you what appears to be a single point of focus – your target. The crosshairs in the scope are superimposed on that target through one-third science and two-thirds VooDoo. Generally, if all is right in the world, your crosshairs will be in focus along with the target. There’s no “alignment issue” of the front sight, rear sight, and target. Just look at your target, and if the crosshairs are on it, you’re good to go. Of course, you do have to make sure that your head is aligned with the scope tube. Fortunately, if it’s not, you’ll know it because you’ll see shadow rings instead of a clear circular view of your target area.

Magnification

The real fun begins when you add magnification to the optical device. Now, you can clearly see your target, with those crosshairs superimposed on it, from a much farther distance. That means precision because you can’t aim at a small point that you cannot see. Additionally, most crosshairs in a scope offer a much finer aiming point that iron sights, especially from a distance.

Scopes come with all sorts of magnification options. Some are fixed power which means that a set amount of magnification is always there. A good example is the Burris 2x20mm Handgun Scope. The fixed magnification is ideal for most handgun rounds that have a modest range. There are also hybrid styles like the AR-332 optic. Part red dot and part scope, this prismatic optic has a three-power constant magnification level. That’s low enough for fast short range use like a zero-magnification red dot but powerful enough to give you precise aiming out to several hundred yards on a good rifle. Certainly fixed-power scopes can go to higher magnification too – the military used fixed 10x scopes for decades.

This Burris Veracity high-magnification scope ranges from 4-20x magnification. We’ll be using in this optics series to reach out to small targets at long range.

Other scopes feature variable magnification controlled by the user. For example, the most popular variable over the decades has been a 3-9x optic that, as the name implies, offers 3x magnification at the low end, but can be zoomed into 9x when desired.

Magnification sounds like a great thing, and it is, within reason. As you get into double digits of magnification, things like mirage (heat waves that blur your view) and field of view (how much you can see through the scope) can become issues. As long as you choose the right optic for your shooting scenario, high magnification can be a benefit. You just need to know the tradeoffs.

What the heck is parallax?

To understand parallax, you need to look no further than the speedometer on your car. When you’re driving, you can easily see that the needle is exactly pegged at 97 miles per hour. However, your passenger, looking at the needle from an angle way off your left, sees the needle pointing at a lower speed, maybe 93 miles per hour. That’s because the focal point is a single object – the speedometer needle. Depending on where you’re sitting, it’s relationship to the background behind it will appear different. It’s a similar concept with scopes.

While this explanation is not scientifically approved, I like to envision the parallax issue with optics like this. Imagine you’re shooting a rifle with iron sights. Now remove the rear sight and use only the front one to aim. You are perfectly lined up – the front sight and your eye are aligned and the target is superimposed on your sight picture. Now, without moving your rifle, move your head to the right a few inches. Your rifle is still aimed right at the target. However, your view shows your aim to be to the left of the target. That’s because you moved the “rear sight” which in this case was your eye.

A rifle scope has only one point of reference – the crosshairs. So, in theory, if you move your head sideways a bit, the crosshair can also appear to shift relative to the target.

Scopes appropriate for shooting past a couple hundred yards generally have an adjustment to minimize parallax. This 3-20x Burris Veracity has a parallax adjustment dial on the left side that is set for a distance of 400 yards.

Fortunately, at lower power, while parallax exists, it’s not really a huge problem. At low power levels and ranges less than a couple hundred yards, it would be challenging for a parallax induced miss to be more than an inch or so. At higher magnification levels and longer ranges, the issue is worthy of consideration. That’s why many higher magnification scopes have parallax adjustments to minimize the problem.

When to choose a magnified scope:

Certainly anytime you need to shoot at extended ranges of 200 yards or more, a magnified scope makes all the difference. While you can hit targets out to 500 (or more) yards with iron sights or a red dot sight, precision will suffer and it will be hard to realize the true capabilities of your rifle. For example, if you have a rifle capable of shooting one minute of angle groups, then that’s about 10 inches at a range of 1,000 yards. It’s virtually impossible for your eye to do that using iron sights.

Precision also comes into play. The crosshairs of a good scope will cover far less area on a target than either a red dot or irons, so if your shooting scenario calls for precise aim and placement, a magnified optic is the way to go.

Summing it up: irons or optics?

Many shooters make the mistake of over magnifying for the task at hand. Sure, it’s fun to aim at a Tootsie Pop at 200 yards, and if that’s your shooting game, but all means get a high power scope. Or perhaps you’re into long range varmint hunting. You’ll need pretty big magnification for that too. However, for most recreational and even competitive use like 3 Gun, you just might be better off with less magnification than you think you need.

Heck, the Appleseed Rifleman program will teach you to hit targets 400 yards away with iron sights. If you can do that, you can reach out even further using a basic optic with single-digit magnification. For this reason, I’m a big fan of using 1x (or zero magnification) red dot sights on AR-type rifles. Optically, you can easily hit targets in the “few inches” size range at 100 yards. As an example, consider the Burris FastFire 3 red dot sight. One model has a 3 MOA (Minute of Angle) dot. That means that the dot only covers three inches at 100 yards and six inches at 200 yards. That allows pretty good precision considering the speed and field of view benefits of zero magnification. As zero magnification red dot sights allow you to focus on your target, they couldn’t be simpler and there is no need for “front sight focus” discipline as with irons.

With new optics mounts and super small red dot sights, you can always choose magnification and red dot sights. This AR-332 is a fixed 3x optic that accepts a Burris FastFire 3 mount on the top. Just tilt you head up and down to quickly switch between sighting options.

If you choose to go the magnified scope route, think about your most likely shooting scenarios. What size target do you need to hit and from what range? Do you need variable power for precise target identification and ability to “dial back” for increased field of view? Will you ever want to shoot at very short ranges, like 50 yards or less? Generally speaking, I might recommend looking at less magnification, rather than more, for your most common anticipated uses.

Next time we’ll get deep into all those mysterious technical terms and concepts, like focal planes, objective lenses, exit pupil, and all the other features that scope manufacturers talk about.