the new Iron Frame Henry in .44-40 faithfully recreates the classic 1860 original, but in a more practical chambering than the original .44 Henry.

To learn more, visit https://www.henryrifles.com/henry-rifles/.

To purchase on GunsAmerica.com, click this link: https://www.gunsamerica.com/Search.aspx?T=henry%20iron%20frame.

There are some true classics that survive the times due to their popularity, capabilities, etc. Guns such as the Single Action Army may be technologically outdated today, but that does not mean there is no demand for them. That is why Colt (and many other manufacturers) are still churning them out.

The new Iron Frame Henry is the first of its type to be manufactured here in the United States for more than 150 years. Image courtesy of Henry Repeating Arms.

Another good example is the 1860 Henry, a paradigm-shifting lever action that first appeared in the Civil War era and influenced firearm design well into the future. But, originals of this firearm can be rare and expensive. So what about those of us who would like to own one for themselves, one that we can actually shoot?

Well, thanks to the efforts of the modern-day Henry Repeating Arms, there is a solution. The new Original Henry Rifle & Iron Framed Original lines from the company are accurate to the originals in every practical detail, making them the first American-made Henry rifles in 150 years. But, before we consider this rifle in detail (and the Iron Frame version I tested), let’s consider the history of the gun itself.

The Henry weighs 9 pounds (empty) and recoil with .44-40 black powder rounds is almost nil, making for quick handing and fast reloading.

SPECS

- Chambering: .44-40

- Barrel Length: 24-1/2 inches

- OA Length: 43 inches

- Weight: 9 pounds

- Stock: Fancy American Walnut

- Sights: Folding ladder rear, blade front

- Action: Lever

- Finish: Case colored frame, blued barrel

- Capacity: 13

- MSRP: $2,750

The Beginning

A fundamental change in American arms making arose from Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson’s early collaboration in the 1850s. This series of events began with Smith and Wesson establishing the Volcanic Repeating Arms Co. in 1855. When the company fell on hard financial times they sold out and formed S&W where they developed their first breech-loading, bored through cylinder .22 caliber revolver. For Horace Smith and D.B. Wesson, the rest of that tale is American firearms history. The failed Volcanic Repeating Arms Co. was taken over by Oliver Winchester and renamed the New Haven Arms Co. in 1857. It was Winchester who tasked Benjamin Tyler Henry with improving the design of Smith and Wesson’s Volcanic rifle. Thus, New Haven Arms was the last leg of a journey leading to Oliver Winchester creating the Winchester Repeating Arms Company 150 years ago in 1866.

The similarity between the Volcanic repeating pistol frame and barrel (below) with that of the Henry rifle are unmistakable. Image courtesy Rock Island Auction Co.

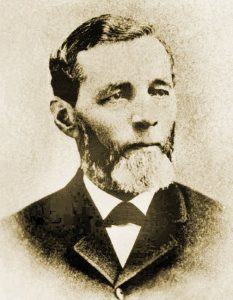

Benjamin Henry Tyler was the genius behind the Henry rifle design, a firearm that was truly revolutionary at the time of its introduction.

The Volcanic Repeating Arms Co. had several shareholders the largest of which had been Winchester. When the Volcanic Repeating Arms Co. hit the financial skids in 1857 he stepped in and took over, acquiring all of its assets. The New Haven Arms Co. of New Haven, Connecticut, had a singular goal: Perfect the design and manufacturing of the brass-framed Volcanic repeating rifle. Winchester also hired inventor/gunmaker B. Tyler Henry as his plant superintendent, and this was not by chance. Winchester knew Henry had helped Smith and Wesson develop the Volcanic, thus he was intimately familiar with the design and its failings. Henry unfortunately had to explain to Winchester that there was little more that he could do to improve the existing guns. Deferring to Henry’s experience Winchester asked him to redesign the rifle. It took Henry three years to accomplish this task but in 1860 he presented Oliver Winchester with the repeating rifle the Volcanic could never be—a magazine-fed, breech-loading, lever-action. Patented October 16, 1860, Winchester named the new rifle after its inventor along with the new .44 caliber rimfire cartridge it was designed to fire. Winchester’s intension was to manufacture both the rifle and the ammunition it fired.

A Nation at War with Itself

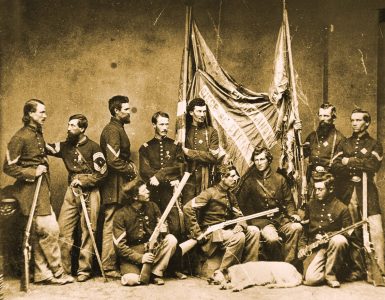

One of the most famous Civil War photographs showing the Henry Rifle. Image courtesy R.L. Wilson, from his book Winchester An American Legend.

The start of the Civil War in 1861 made the Henry rifle one of the most admired and feared weapons in the hands of U.S. troops, and one of the most coveted prizes for any Confederate soldier (along with a cache of .44 Henry rimfire ammunition). Ironically, the U.S. War Department did not purchase very many Henry rifles for Federal Troops, a total of 1,731 in 1863 for the 1st D.C. Cavalry. The majority of individual soldiers and units purchased them at their own expense in deference to the Ordnance Department’s decision not to issue the rifles to troops in the field. This came much to the chagrin of Chief of Ordnance, General James W. Ripley, who had essentially snubbed Oliver Winchester when he first approached the Ordnance Department offering to sell the U.S. military his new repeating rifle. Ripley regarded the Henry as less than ideal for combat use because it had an open follower slot on the lower side of the magazine tube. In Ripley’s opinion it could be easily clogged with the dirt, mud and other debris encountered in battle, thus making the arm inoperable. In point of fact, he was right; the Henry did have a propensity to jam if not carefully maintained in the field. It was one of the design’s three notable shortcomings; the other two were the slow reloading process and the absence of a wooden forearm. One also had to be aware of one’s hand position on the magazine and barrel as the follower moved back with each successive shot. And since there was no wooden forearm when the barrel became hot after repeated firing it was hard to hold, leaving a soldier to either wrap his hand with a rag, wear a glove, or endure the hot barrel. The Henry was not a perfect design, however, what Ripley and government inspectors failed to realize was that in a skirmish, one properly functioning Henry was worth a dozen soldiers armed with the Army’s single-shot percussion U.S. Rifled Muskets. More to the point, during the Civil War, when the average soldier armed with a rifled musket was expected to load and discharge his weapon up to three times per minute, a small unit armed with Henry repeaters could nearly provide the sustained firepower of an entire company. Yet Col. Ripley’s opinion was that no better weapon could be issued to soldiers in the field than the rugged single-shot, .58 caliber, U.S. rifled musket. Unfortunately, he never asked those soldiers in the field for their opinions, and no one, except soldiers in the field, truly recognized the value of the 16-shot, .44 rimfire Henry repeater in combat. Confederate troops on the receiving end of Henry repeaters certainly did and began calling it “That damned Yankee rifle you can load on Sunday and shoot all week.”

Why a .44?

While the original was chambered for the .44 Henry round, the new rifle fires the readily available .44-40 round.

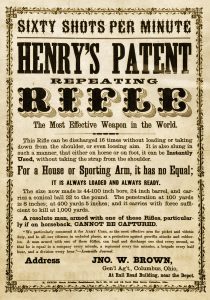

Although the .44 cartridge was considered underpowered (compared to other rifles in use at the time) the Henry, when fired by a trained marksman, using a well cared for and smoothly operating rifle, could inflict more damage at a greater distance to an enemy line in less time than a dozen infantrymen firing U.S. Rifled Muskets. Winchester’s sales agent John W. Brown in Columbus, Ohio, boldly claimed in advertising that “a resolute man, armed with one of these rifles, particularly if on horseback, CANNOT BE CAPTURED.” While this tidbit of marketing hyperbole was a little optimistic, it wasn’t too far-fetched. During the War Between the States, Union soldiers armed with Henry lever-action rifles decided many a skirmish. The sustained firepower unleashed by the Henry Rifle was described by Union Major William Ludlow’s in his account of the Battle of Allatoona Pass, fought October 5, 1864, in Bartow County, Georgia. “What saved us that day was the fact that we had a number of Henry rifles. This company of 16 shooters sprang to the parapet and poured out such a multiplied, rapid and deadly fire, that no men could stand in front of it and no serious effort was made thereafter to take the fort by assault.”

The author found the new Henry to be a faithful recreation of the original, and very pleasant to shoot.

Despite similar accounts from the field, the prevailing military rifle round (single shot) remained the .58 caliber, a large, stout lead ball that, when it struck home, was capable of inflicting a devastating wound. Using a paper cartridge or lead ball rammed down the barrel of a Rifled Musket, .58 caliber round ball was as close to a standardized rifle load as the U.S. could manage. There were many other rifles used by the Union during the war and in varying calibers, thus the supply line of varying ammunition was always thorny. When designing the Henry rifle, B. Tyler Henry had regarded the .58 caliber round as too large a caliber for a self-contained cartridge to fit the repeaters lever action design, thus he had chosen to chamber it in the largest caliber possible for the rifle, .44 caliber. The .44 Henry rimfire cartridge proved an adequate enough round, given that the rifle was capable of exceptional accuracy, and could provide a soldier with 15 rounds ready in the magazine plus one in the chamber. Being a practical man, Henry had chosen capacity and sustained firepower over cartridge size, but the Ordnance Department didn’t agree. Christopher Spencer came closer to the government’s standard with his .56-50 caliber Spencer repeating rifle, which was slower in operation (having to manually cock the hammer for each shot) and it had a lower magazine capacity, but had proven more rugged than the Henry, and the Spencer had an enclosed magazine inside the buttstock. The U.S. military favored this rifle (and carbine) over the Henry, ordering 107,000 during the Civil War.

From Volcanic to Henry

The Henry proved to be capable of rapid fire due to its lever-style action that would eject a fired case, cock the hammer and load a new round.

The Henry’s internal mechanism was adopted from the Volcanic with the toggle link design moving horizontally to the rear during the downward motion of the finger lever, thus driving the bolt to the rear to cock the hammer while the spent shell case was extracted, and then forward with the closing of the lever to chamber a new round from the magazine tube. However, the horizontal movement of the toggle link in relation to the size of the receiver limited the length of travel and the size of the cartridge case that could be loaded or extracted; the underlying reason Henry had designed the short .44 caliber Henry Rimfire cartridge. This same design was also used in the Winchester Model 1866 (also originally chambered in .44 Henry rimfire), the famous Winchester Model 1873 and all Winchester lever actions up until the introduction of the John M. Browning designed Model 1886, which introduced a new type of lever action mechanism.

During the Civil War the relationship between Oliver Winchester and Benjamin Tyler Henry had begun to deteriorate and the growing acrimony between the two men reached its boiling point in 1865 when Henry attempted to oust Oliver Winchester from the company. Henry briefly succeeded in taking control of New Haven Arms but Winchester still held the purse strings and simply withdrew, and in so doing took all of the company’s assets with him, along with B. Tyler Henry’s plant superintendent, arms designer Nelson King. With King’s patents for improving the Henry in hand, in 1866 he reorganized New Haven Arms into the Winchester Repeating Arms Co.

One of many Henry advertisements during the War Between the States. Image courtesy R.L. Wilson, from his book Winchester An American Legend.

No longer in Winchester’s employ, B. Tyler Henry spent the rest of his life as a gunmaker, never again achieving the success he had known during his tenure at New Haven Arms, Co. He died in 1898 at age 77. He did, however, manage to outlive Oliver Winchester, who preceded him to the hereafter in 1880. But Benjamin Tyler Henry’s eternal legacy, however bittersweet he may have found it, would be the gun he designed for Oliver Winchester in 1860.

The New Haven Arms Co. began manufacturing the Henry in 1860 with the first models produced having an iron frame, rather than the better known brass frame. The Iron Frame Henry was serialized in their own range, from 1 up through approximately 400, (although the serial numbers of known Iron Frame Henry rifles range from 2 to 355). Iron was also used for the butt plate, and the finger lever had no provision for the locking latch seen on the later brass frame Henry models produced through 1866. With the brass frame, production numbers started again at serial number 1 and concluded in the 14,000 range. The Iron Fame was and remains a rarity, uniquely distinguished from the brass frame models that succeeded it.

With thousands of Civil War-era Henry lever action rifles in the hands of ex-soldiers, frontier lawmen, cowboys, outlaws, and farmers, along with the new brass frame Winchester Model 1866 arriving fast on its heels, the Winchester lever action rifle was destined to become “The Gun That Won The West.” Even the old Henry rifles remained in use well throughout the end of the 19th century and were still seeing use in the early 20th century.

An Original from an Original

When Anthony Imperato, president of Henry Repeating Arms Co., decided it was time to reproduce an original Civil War era Henry lever action rifle, he went out and purchased an original rifle manufactured in New Haven in 1865. The well-worn repeater, serial number 8261, was then disassembled and used to reverse-engineer Benjamin Tyler Henry’s classic design and develop the tooling for the new Original Henry Rifle & Iron Framed Original line. The rifle sports a one-piece 24½-inch octagonal barrel with tubular feed magazine, a genuine American fancy walnut buttstock, and a classic folding ladder rear sight paired with a traditional blade front sight. There are two variants: The H011 with a brass receiver, and the H011IF with an iron frame receiver (tested here).

Like the original, the new Henry Iron Frame has a storage compartment in the buttstock for a cleaning rod. Early Henrys had a two-piece hardwood rod with ferrules threaded at both ends.

The new Original Henry Iron Frame model variant handles just like the original, with the advantages of modern metallurgy for the color cased frame and butt plate. There is also the addition of the locking latch seen on the later brass frame Henry models, and of course, being chambered in .44-40, since .44 Henry rimfire cartridges are obsolete. Total capacity with the longer .44-40 cartridge is 13 +1, which is a small compromise for the convenience of centerfire ammunition in a comparable caliber. Loading is identical to the original Henry, sliding the follower and compressing the spring to the end of the muzzle, then firmly grasping the front 5-inches of the barrel and magazine and rotating them to the left to lock the follower and spring back and expose the loading channel in the magazine. Rounds are then carefully loaded with the rifle held at an angle. When the magazine is filled, the upper portion of the barrel and magazine are rotated back into place while allowing the follower to gently rest on the top cartridge. One can quickly see the drawback to this process in the heat of battle! Nelson King’s frame-mounted loading port and the enclosed magazine tube on the Winchester Model 1866 perfected the Henry design. Still, there is much to be said for a classic like the Iron Frame Henry, and shooting this hefty 43-inch-long, 9-pound lever action rifle is as close as one can get to loading and firing an original.

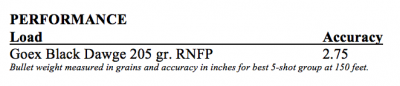

To get the true experience with the Iron Frame Henry I went over to the dark side and loaded it with Goex .44-40 Black Dawge 205 gr. black powder rounds. It’s loud, it’s smoky and it’s authentic! Weighing 9 pounds, recoil is almost non-existent. Back in the 1860s, the Henrys were known for their long-range accuracy. I opted to shoot the test at 150 feet (50 yards) from a man-sized target. All test shots were fired offhand from a kneeling position. Before the range test I chronographed the Black Dawge rounds at an average velocity of 1,069 fps (feet per second) measured 10 feet from the muzzle.

Trigger pull on the Henry averaged 8 lbs.-12 oz. and the lever action functioned smoothly, quickly kicking empty shells up and off to the right. There were no failures to function and the Henry’s balance in the hand from a kneeling position was excellent. And as previously noted, with .44-40 black powder rounds recoil is almost nil, making the gun quick to handle and get back on target.

At 150 feet shots were just a little above point of aim with my best 5-round groups measuring 2.75 and 3.1 inches. Out of 30 rounds (loading only 10 into the magazine each time) every round fired struck within the target’s center body mass. With practice, once can easily fine tune their sighting with this rifle and consistently keep groups under 2.5 inches at this range and certainly out to at least 100 yards. Civil War marksmen were known to hit their target out to 1,000 yards with a Henry! The bottom line is that this rifle is true to the original, with all its shortcomings and advantages. With a suggested retail price of $2,750 it not an inexpensive gun, but owning a Henry Repeating Arms Original Henry Iron Frame is more than owning a rifle, it is a little piece of American history.

To learn more, visit https://www.henryrifles.com/henry-rifles/.

To purchase on GunsAmerica.com, click this link: https://www.gunsamerica.com/Search.aspx?T=henry%20iron%20frame.