When I was a kid the adage was that “a mule deer buck will always stop to look back.” We considered them slightly slow cousins to the whitetail—much easier to hunt. You just had to go where they lived and the big bucks would stand out in the open and stare at you.

This may or may not have been true. A classic Baby Boomer, I started hunting in the latter phases of the post-World War II era, which was also “the golden age of mule deer hunting.” Mule deer populations were at all-time highs in much of the West. Taking a really big mule deer was just a matter of going into the high country, or so goes the legend. You can’t prove it by me because I didn’t take any big mule deer when I was a kid. Dad and I tried, sort of. In the mid-sixties and early seventies, we hunted mule deer in Colorado, Montana, and Wyoming, which was by most accounts at least the tail end of the “golden age.” However, we were eastern Kansas bird hunters. We didn’t know what we were doing, and any buck with antlers looked pretty good. Dad and I didn’t take any decent bucks until much later, and by then big mule deer were scarce.

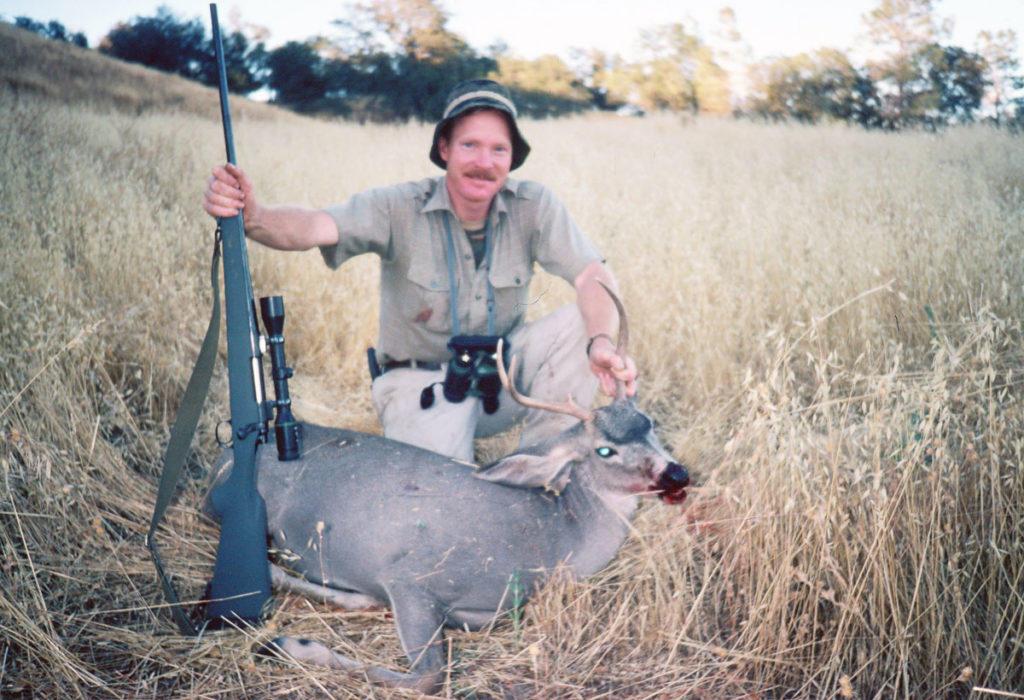

My first good buck—not a giant—came in northern Nevada in 1978. The aridest state, Nevada went to tags-by-drawing earlier than most western states. As a result, they’ve maintained a high buck-to-doe ratio and good age-class distribution. Forty years ago those tags were easier to draw than they are today!

1978 Nevada: The end of a long day in northern Nevada, 1978. I’m not sure who is in the worst shape, me, the horse or the buck. Although no giant, this was my first big mule deer, at the very tail end of the “golden age” of mule deer hunting.

Mule deer populations peaked at different times in different areas, and likewise when they hit bottom. The long downhill slide of mule deer across the West is well-known. Predation, loss of winter range, human development, sagebrush eradication, competition from increasing elk, perhaps all this and more. Less well-known is that this is ancient history. Mule deer populations today are healthy across most of the West. Overall numbers are up and biologists tell us management goals are being met. I don’t question this, but why are big mule deer so hard to find?

2008 Wyoming mule deer: A great mule deer taken on my friend Tom Arthur’s Wyoming ranch, in sagebrush country far from the big mountains. All Wyoming nonresident mule deer permits.

Co mule deer: A fine mule deer buck, taken in southeastern Colorado. The high plains east of the Rockies and the western edge of the Great Plains are excellent mule deer country from north to south.

I lack the expertise to properly answer this question. However, it’s both good and not so good that, to some extent, wildlife management in North America is a numbers game. Good because, on public lands, we enjoy the greatest hunting opportunity of any people on Earth, and this has created the world’s largest hunting culture. Not so good in that, because of the way our system was established and is maintained, our state and provincial game departments rely on that large license-purchasing hunting public. Unusual circumstances created those long-gone golden years of mule deer hunting. There was little recreational hunting during the Great Depression and less during World War II. Mule deer country had smaller human populations and less development. Mule deer are less adaptable than whitetails. Winter range is critical, which renders them more sensitive to the vagaries of drought and bad winters.

Tom Arthur glassing classic mule deer country on his Wyoming ranch. Patient glassing is almost always the best way to locate mule deer bucks.

The genetics that once produced big mule deer in numbers are still there, but it takes time for bucks to reach full antler development. There is more hunting pressure today and more competition for permits. Across the width and depth of mule range, big mature bucks cannot again be as large a percentage of the herd as they were in the fifties and sixties.

There are, however, still great places. Today, most Western states manage some areas for trophy bucks by limiting pressure while other areas are managed for higher production. Both goals are perfectly valid: Venison for the freezer, and big antlers plus venison for the freezer. In fact, both goals are essential because that’s the way our North American model of wildlife conservation works. But it must be accepted that, in mule deer country today, it is not possible to produce enough big antlers for everyone.

I believe strongly in our permit draw systems. Hunters in good standing have equal opportunity and only one thing is certain: If you don’t apply you will not draw. Realistically, however, even with today’s preference point and bonus point systems, it can take years to draw some of the really good mule deer tags.

Terry Moore and Craig in South Dakota: Terry Moore and me, a great day in western South Dakota with two nice mule deer bucks.

I’ll be honest: I don’t apply in “great” mule deer areas. My fear is I might draw and not be able to go, thus wasting a precious opportunity. However, it depends on your interest: I stay in sheep and goat drawings because, for me, those are “drop everything and go” opportunities. There are also many excellent private land opportunities and a few on reservations. These can be awesome for big mule deer, but they can be pricey. I rarely indulge. I love mule deer and mule deer country, but I’m not a mule deer specialist and, after all, I’ve had plenty of chances in the last half-century.

In recent years I’ve done little mule deer hunting in classic alpine habitat. Today there’s a lot of competition from elk in the high country so, instead, I’ve done most of my hunting around the edges. Across much of the West, mule deer numbers are up in the breaks, badlands, and high plains surrounding the big mountains. The legend is that “plains mule deer” grow spindly antlers, but I don’t think this is true. Far more important is that bucks are allowed to grow up and reach full maturity. Eastern Colorado produces superb mule deer all along the Rocky Mountain Front all the way to Kansas. This holds true all across the western Great Plains. I’ve had productive mule deer hunts in western South Dakota, and in eastern Montana and Wyoming far from high country.

Jim Rough and me with a nice old mule deer. This is what you might call a “character” buck with lots of mass, no giant but a good buck.

Interesting “sleeper” spots include the Texas Panhandle and the prairies of southern Alberta, but finding a big mule deer is always a matter of weather and timing. You can’t do much about the weather, but I always hope for fresh snow to get deer moving. Sometimes you can’t do much about timing, either! Hunting season is what it is, but avoid the full moon if possible. And, although we all want to catch opening day, later is often better. Rutting activity is unlikely in October and early November, but the rut is almost certain to kick in around Thanksgiving.

Donna Boddington took this beautiful four-by-four mule deer in Wyoming. In today’s mule deer country this is a buck one should think about hard before passing.

Realistic expectations help. No areas I know of hold a lot of big bucks, but that depends on your definition of “big.” A mule deer qualifying for the Boone and Crockett records isn’t just the buck of a lifetime–many of us will never see one. However, for every monster, there are quite a few impressive four-by-four bucks. Set your goals as you will, but pass nice bucks at your peril!

Most mule deer hunting is weather-dependent. You can’t control the weather, but some fresh snow it usually a blessing when it happens.

Persistence sometimes counts. I was fishing for salmon at buddy Jim Rough’s Black Gold Lodge in coastal British Columbia when he showed pictures of awesome bucks he’d taken in the prairie country of southeastern Alberta. Alberta has a weird system whereby outfitters “own” the nonresident permits. Duane Nelson owned these permits so we tried three times. The first year we caught a freak blizzard, ranch roads impassable. The next year wind blew 50 miles per hour. I knew we were in trouble when, on the drive down from Calgary, we passed tractor-trailers rolled over in the ditch. We found deer in deep coulees, out of the wind, but no big boys. Still, I thought we were in the right place, so we tried a third time. Our first day, in mid-November, dawned clear, cool, and calm. With little effort, I shot my ‘best-ever” mule deer. It occurred to me that maybe I shouldn’t shoot on the first day, but the thought passed quickly. A storm came in the next day and we were lucky to make it back to Calgary. On big mule deer, when opportunity knocks it’s wise to open the door!